Cleanup Begins: Bihar Targets Fake Votes, Real Illegals

Door to door verification of India’s voter lists has begun for the first time in over two decades as the Election Commission of India (ECI) launches a special intensive revision across six states. This unprecedented verification process comes 20 years after the last intensive revision was conducted in Bihar in 2003. Consequently, approximately 7.9 crore voters in Bihar alone are now under scrutiny, with an estimated 20% of voters—nearly 1.6 crore to 2 crore people—potentially being removed from the electoral rolls.

The Election Commission’s door to door campaign aims to ensure the integrity of voter lists in Bihar, Assam, Kerala, Puducherry, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal. Notably, this comprehensive door to door survey is being conducted under Rule 31 of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960. The ECI cites multiple factors necessitating this intensive verification, including rapid urbanization, frequent migration, deaths not being reported, and increasing cases of fraudulent voter registrations. In addition, the inclusion of names of foreign illegal immigrants has made this verification essential for maintaining the purity of electoral rolls.

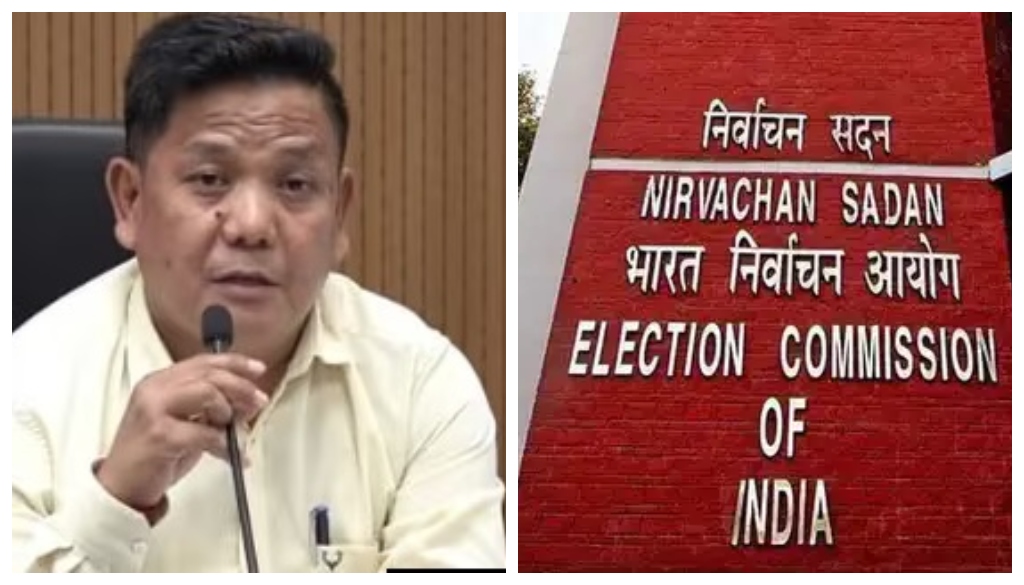

EC launches door-to-door campaign to verify voter rolls

The Election Commission has mobilized an unprecedented workforce to execute its ambitious door-to-door verification campaign across Bihar. Currently, 77,895 Booth Level Officers (BLOs) are visiting households throughout the state, helping residents complete enumeration forms and collecting them on the spot.

Furthermore, the Commission is appointing an additional 20,603 BLOs to ensure timely completion of this extensive process. When BLOs visit homes, they verify voter identities, assist with form completion, and in many cases, take live pictures of electors and upload them immediately—saving citizens the trouble of obtaining photographs themselves.

This door-to-door survey follows a structured approach. BLOs must visit each residence, and if a house is found locked, they are instructed to slip the form under the door and return at least three more times to collect it. Bihar’s 7.73 crore voters have until July 26 to submit their completed enumeration forms.

Beyond the BLOs, the campaign has engaged nearly 4 lakh volunteers drawn from government officials, NCC cadets, and NSS members to assist elderly, disabled, sick, and vulnerable populations with the verification process. Overseeing this massive door-to-door campaign are 239 Electoral Registration Officers (EROs), 963 Assistant EROs, and 38 District Election Officers who are working at ground level to facilitate form submission.

Recognizing the extensive effort required, the Chief Electoral Officer of Bihar has announced a special incentive of Rs 6,000 for each polling station official involved in the campaign. This financial acknowledgment underscores the scale and importance of the verification effort.

The door-to-door approach represents one of the most personal ways to engage citizens with the electoral process. According to electoral experts, such campaigns serve multiple purposes: sensitizing public awareness about voting rights, providing information about registration processes, and enabling officials to record complaints or concerns from citizens.

During these visits, BLOs focus on multiple verification activities: registering previously unregistered voters, verifying Elector Photo Identity Cards, identifying outdated black and white image cards for replacement, enrolling new voters who turned 18 by July 1, 2024, and updating records for voters who have relocated or deceased.

This intensive door-to-door campaign reflects the Election Commission’s commitment to maintaining accurate electoral rolls across the country.

EC Rolls Out Document Crackdown: Aadhaar, PAN, and Voter ID No Longer Enough

The Election Commission’s intensive verification effort has introduced stringent documentation requirements for voters not listed in the 2003 electoral rolls. At the heart of this process is a list of 11 specific documents, significantly more restrictive than normal voter registration requirements.

For voters whose names are absent from the 2003 electoral rolls, the Commission requires at least one document from this list to establish eligibility. These include birth certificates, passports, matriculation certificates, permanent residence certificates, forest rights certificates, caste certificates, family registers prepared by state authorities, and government-issued land allotment certificates. Moreover, any identity documents issued to government employees or pensioners, or documents issued by government authorities prior to July 1, 1987, are also acceptable.

The requirements vary based on when a person was born. Those born before July 1, 1987, must provide proof of their own place and date of birth. Individuals born between July 1, 1987, and December 2, 2004, must additionally submit documents for either parent. For those born after December 2, 2004, proof for both parents becomes mandatory.

Essentially, the EC has created a tiered system where approximately 4.96 crore out of Bihar’s 7.89 crore registered voters—those already listed in the 2003 electoral rolls—are exempt from submitting additional documents. These voters only need to verify their details from the 2003 Electoral Rolls.

Specifically absent from the accepted documentation list are commonly used identity documents. Aadhaar card, PAN card, MGNREGA job card, voter identity card, driving license, and bank passbooks are not acceptable for this special verification process.

The Commission has attempted to ease concerns, clarifying that if a person’s parents are listed in the 2003 electoral roll, they need not provide parental documents even if born after 1987. Additionally, the Bihar Chief Electoral Office has stated that voters can still get verified without the mandatory documents through local investigation by Electoral Registration Officers.

This documentation mandate represents an unprecedented shift from standard voter registration procedures, where documents like Aadhaar, PAN, and driving licenses are typically accepted as valid proof of identity and address.

Not NRC, Not Political — Election Commission Defends Voter Cleanup Amid Uproar

Amid growing criticism from opposition parties, Chief Election Commissioner Gyanesh Kumar has strongly defended the special intensive revision of voter lists. Kumar emphasized that updating voter lists before elections is a legal requirement and follows established precedent. The last intensive revision in Bihar was conducted over 31 days from July 15 to August 14, 2002, while the current process spans the same 31-day period from June 24 to July 25, 2025.

“Nearly every political party complained about issues in the authenticity of the voter list and demanded updates,” Kumar stated, highlighting that the Election Commission had conducted approximately 5,000 meetings with political parties over the past four months, involving around 28,000 party representatives.

Nevertheless, opposition parties have intensified their criticism. Bihar Congress president Rajesh Kumar called the exercise a “conspiracy” targeting voters from marginalized communities. Similarly, RJD spokesperson Chitranjan Gagan alleged the process would deprive “Dalits, backward classes, extremely backward classes, and minorities” of their voting rights.

In response, the Election Commission has clarified that individuals whose names appeared in the 2003 voter list will be considered “prima facie eligible” under Article 326 of the Constitution and are exempt from submitting additional documents. Their children applying for voter registration would likewise be exempt from parental documentation requirements.

The Commission has emphasized transparency throughout the process, providing free copies of draft and final electoral rolls to recognized political parties and publishing weekly lists of claims and objections. Furthermore, the EC maintains that electoral rolls are prepared following well-defined protocols with political party participation at every stage.

Despite these assurances, West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has compared the exercise to the National Register of Citizens, calling it “more dangerous”. However, commission officials have explicitly stated that Electoral Registration Officers cannot decide on citizenship matters and will refer complex cases to higher authorities for further inquiry.

EC Tightens the Screws: Voter Proof Rules Intensify Citizenship Scrutiny

This unprecedented voter verification campaign marks a significant shift in India’s electoral management system. The Election Commission’s intensive revision across six states aims to cleanse electoral rolls through meticulous door-to-door verification. Undoubtedly, the potential removal of up to 20% of voters from Bihar’s electoral rolls signals the substantial impact this process may have nationwide.

The Commission justifies this extensive exercise based on multiple factors. Rapid urbanization, widespread migration, unreported deaths, and fraudulent registrations certainly necessitate such verification. Additionally, concerns about illegal immigrants on voter rolls have prompted these stricter measures, particularly the requirement for specific documentation from those absent from 2003 electoral lists.

Despite official justifications, opposition parties remain skeptical. Their concerns primarily focus on possible disenfranchisement of marginalized communities through documentation requirements. Nonetheless, the EC maintains that transparency guides the process, with political parties receiving free copies of electoral rolls and weekly updates on claims and objections.

The massive mobilization of nearly 78,000 BLOs, supplemented by thousands of volunteers and electoral officers, demonstrates the scale of this undertaking. Though controversial, this verification process represents a fundamental attempt to strengthen India’s democratic foundation by ensuring electoral roll accuracy. The final outcome will likely shape electoral participation patterns for years to come, especially among communities struggling with documentation challenges.

As this verification process unfolds across the targeted states, its implementation will face close scrutiny from political parties, civil society, and international observers. The balance between maintaining electoral integrity and ensuring inclusive voter participation remains the central challenge of this ambitious undertaking.